Image: Heteromeles arbutifolia (Toyon), a common chaparral shrub in California. Plant secondary chemistry differs between populations on the California mainland and the nearby Channel Islands.

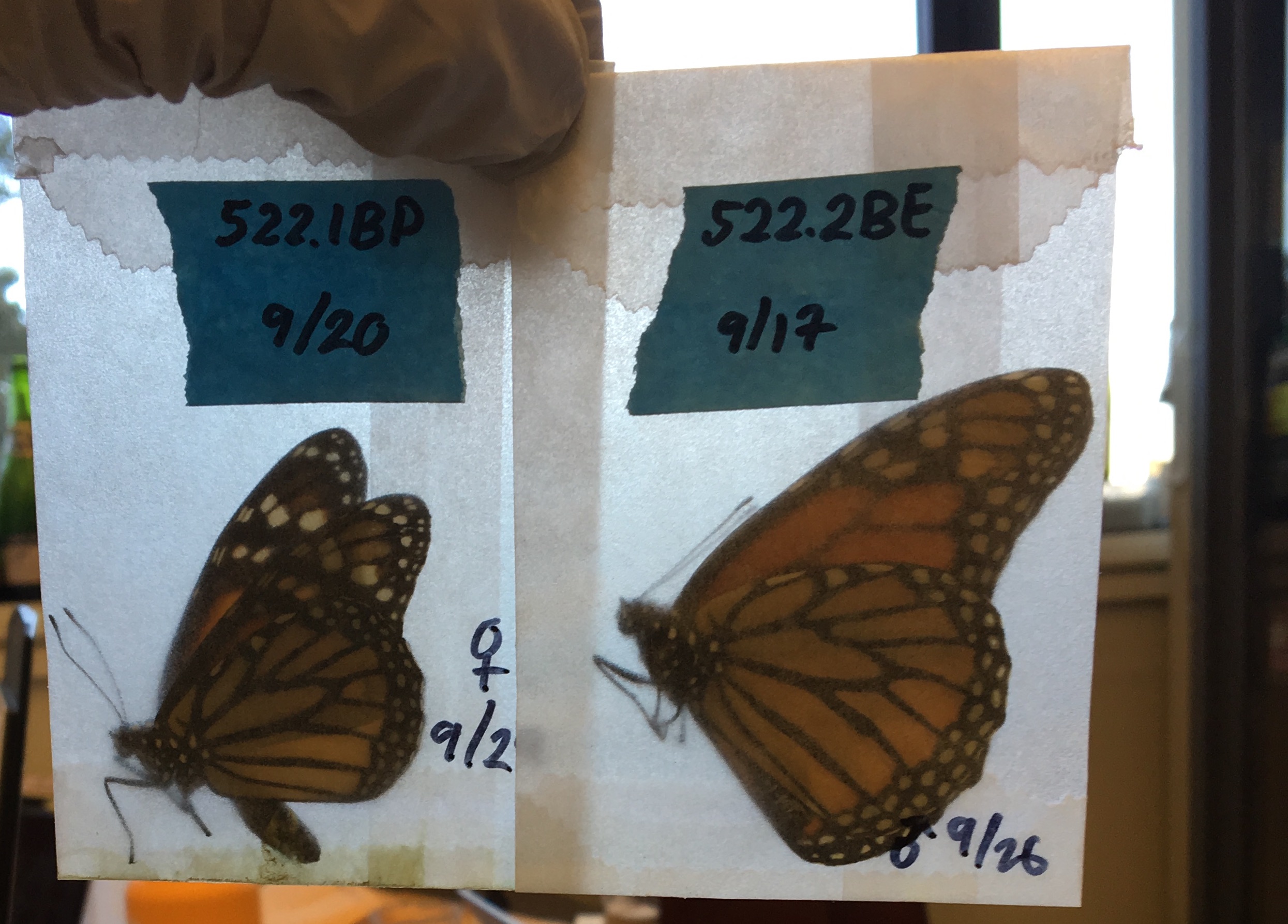

Image: Monarchs from Puerto Rico (left) and North America (right) reared under common greenhouse conditions

Image: A monarch butterfly nectaring on A. curassavica in Guam. Monarchs were first recorded in Guam in 1887.

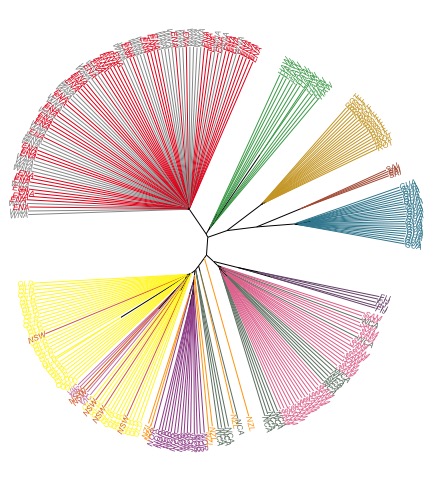

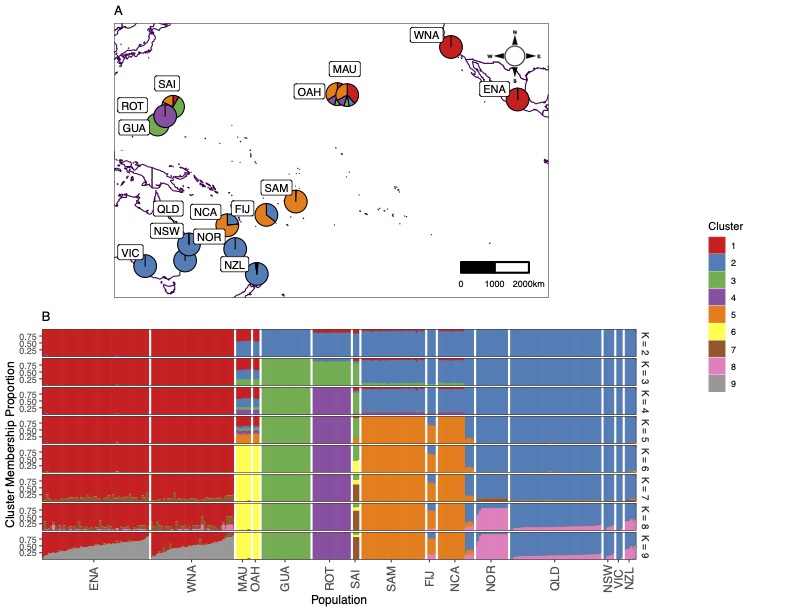

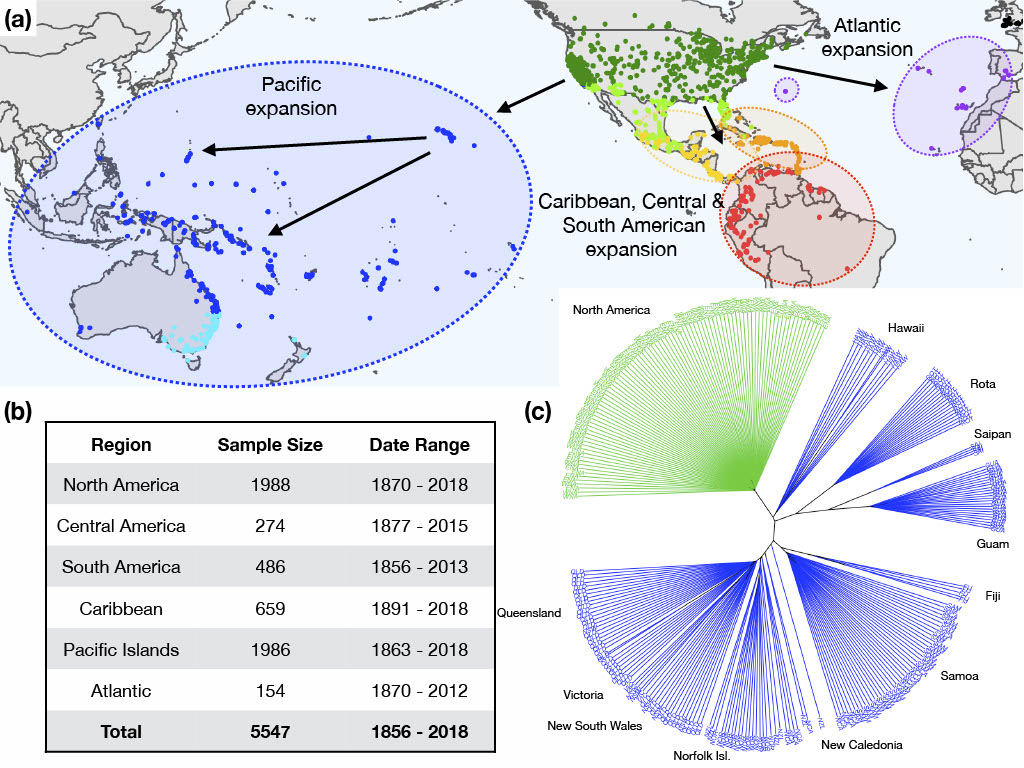

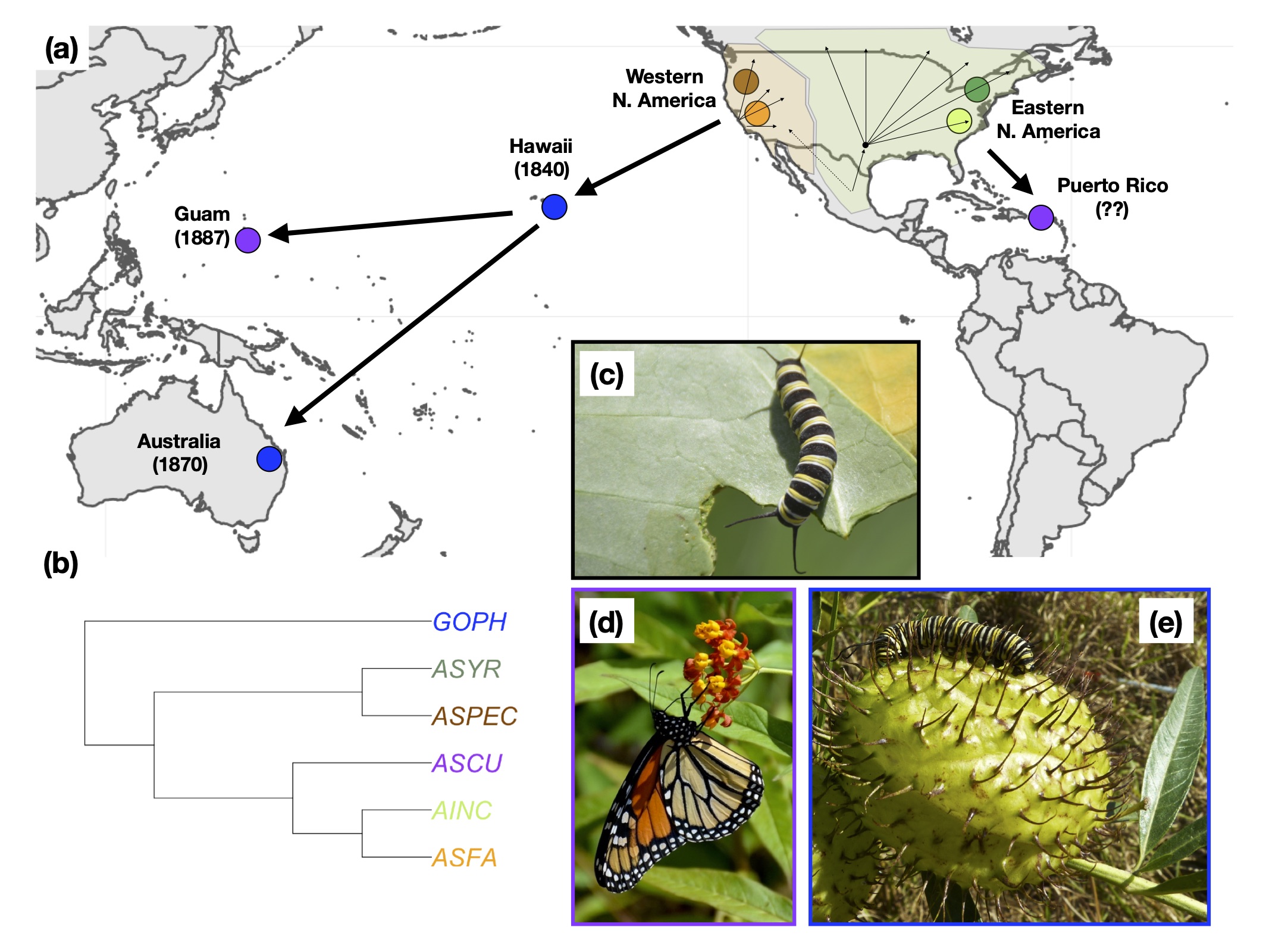

Monarchs are originally from Central and North America but can now be found around the world. When and why did this range expansion occur? How are these populations related to one another?

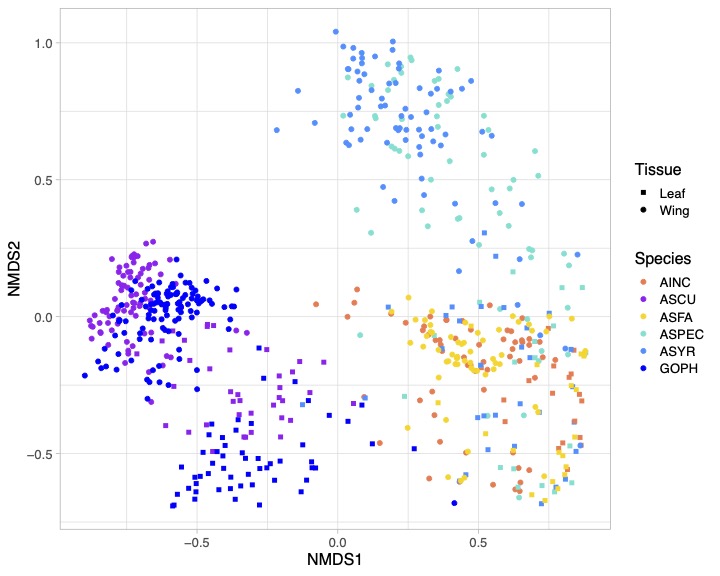

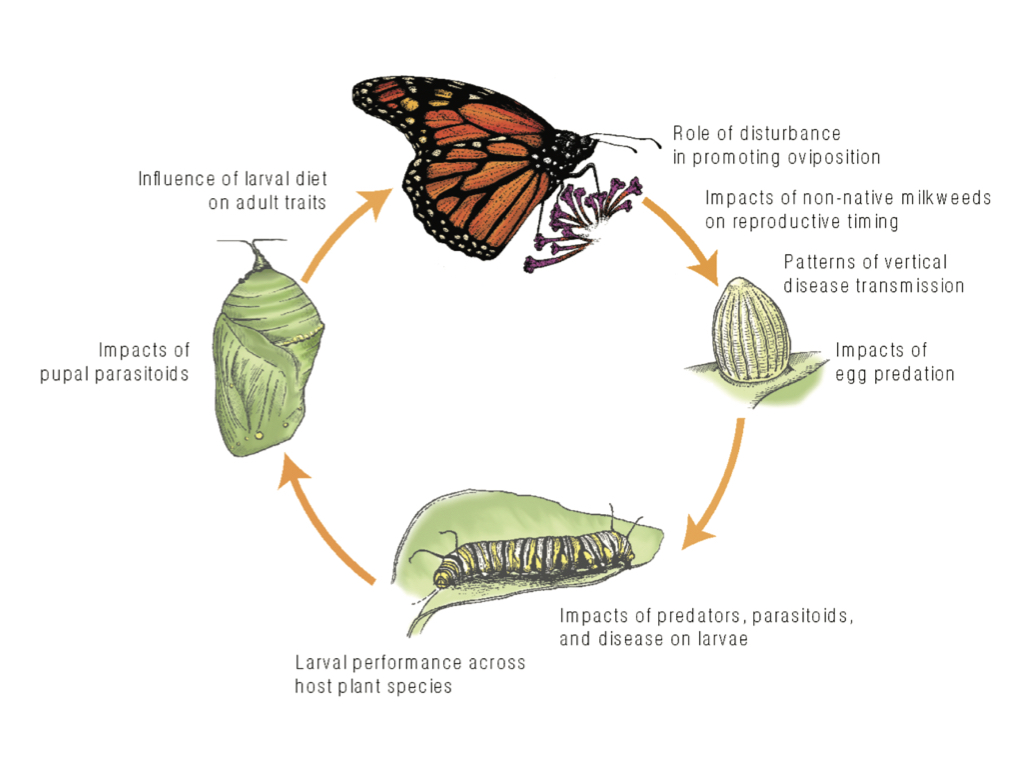

Monarchs feed on milkweed plants as caterpillars. How do cardenolides (toxic secondary compounds) produced by milkweeds influence monarchs and their interactions with natural enemies?

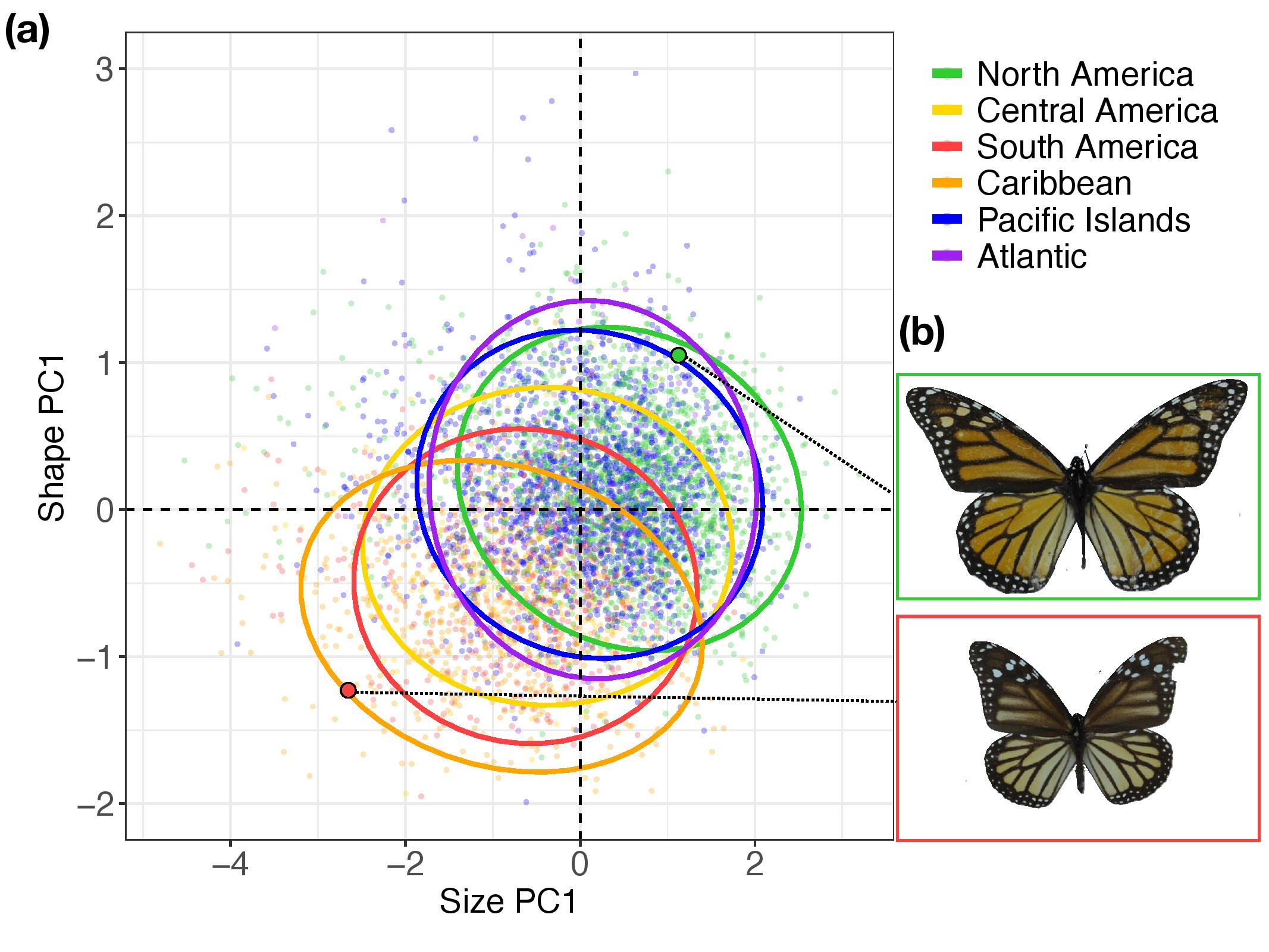

How does does seasonal migration affect morphology and physiology? Can we see contemporary evolution in recently established non-migratory populations?

Click images to access free PDFs. Click paper titles to visit publisher website.

BMC Ecology and Evolution

Novel genetic association with migratory diapause in Australian monarch butterflies

Journal of Pollination Ecology

Increased reliance on diurnal pollination in a geographically and morhpologically atypical sand verbenaPlants

Evidence for reductions in physical and chemical plant defense traits in island floraCover Image - April Issue: Link

Current Opinion in Insect Scince

Migration genetics take flight: genetic and genomic insights into monarch butterfly migration

Proceedings of the Royal Society B

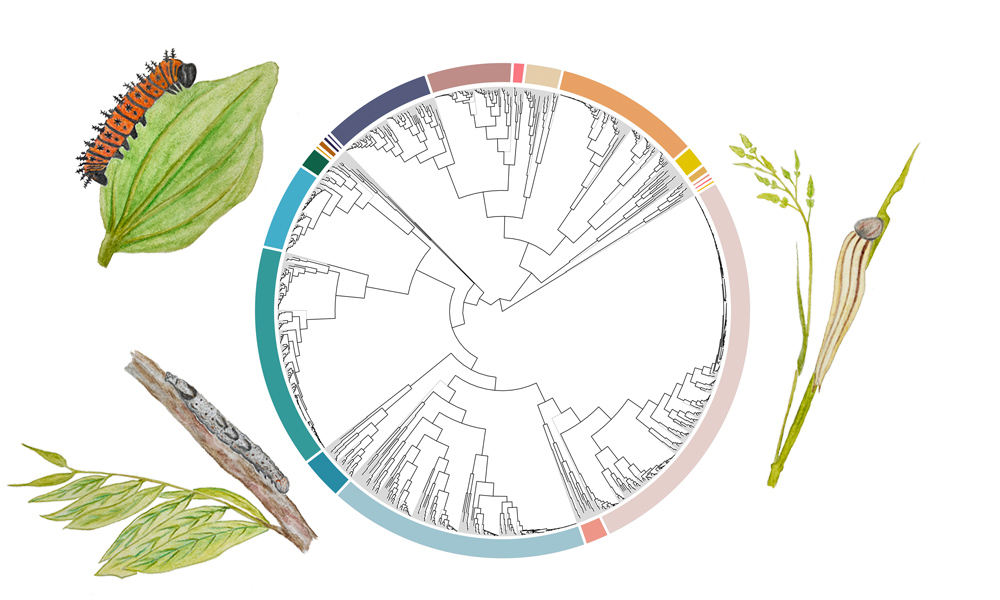

Macroevolution of protective coloration across caterpillars reflects relationships with host plantsCover Image - January Issue: Link

Molecular Ecology

Population genetics of a recent range expansion and subsequent loss of migration in monarch butterflies

Annals of the Entomological Society of America

BioRxiv

Population-specific patterns of toxin sequestration in monarch butterflies from around the world

Conservation Science and Practice

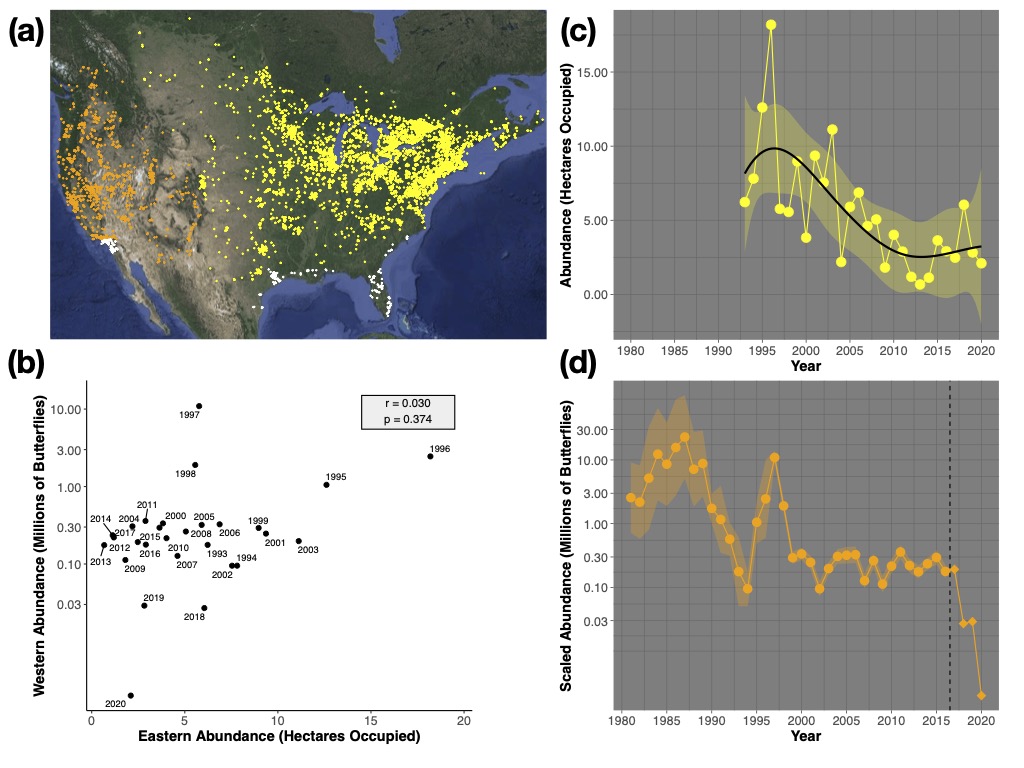

Are eastern and western monarch butterflies distinct populations? A review of evidence for ecological, phenotypic, and genetic differentiation and implications for conservationCover Image - July Issue: Link

PNAS

Two centuries of monarch butterfly collections reveal contrasting effects of range expansion and migration loss on wing traitsPress coverage: UC Davis, Santa Cruz Sentinel, San Jose Mercury News, Davis Enterprise

Evolution

Host plant adaptation during contemporary global range expansion in the monarch butterflyAnimal Migration

Wing morphology in migratory North American monarchs: characterizing sources of variation and understanding changes through timeResearch featured in National Geographic

Oecologia

Landscape-level bird loss increases the prevalence of honeydew-producing insects and non-native antsBiological Journal of the Linnean Society

Non-migratory monarchs, Danaus plexippus (L.), retain developmental plasticity and a navigational mechanism associated with migration